Make sure to checkout A Dynamic Dashboard for Project Durations and Costs in Excel (part 2) for the example file!

Let’s say you are the manager of a portfolio of projects at your company. While each project under your aegis is different, they have a few things in common; specifically – and for the sake of our example – they all go through (or, are currently in) three different phases, and each phase has a different cost per month, but the cost doesn’t differ between each project. In our example, the phases are:

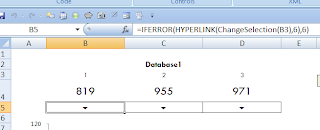

Using a VLOOKUP might seem like an obvious choice for our solution. Here's how to do it.

The Dynamic VLOOKUP Method

Step 1: Create the VLOOKUP table

Since you know there are three projects, you could encode ids into a lookup table numbers as follows.

Step 2: Create a Reference Table

The Reference Table is a time-series table that holds the numerical references to your VLOOKUP table. If IT Services has two months of Planning, then the Reference Table will show two 1's in the first two months, respectively.

Step 3: Create a Values Table to map each reference to its monthly cost using VLOOKUP

Now, you'll make another table that is essentially a mirror image of your Reference Table. This table, however, maps each reference to the correct cost. So, for Month 1 in the Values Table, VLOOKUP will use the corresponding reference (1) in the Reference Table to indicate the project is in the Planning phase and the associated cost is $250.

Step 4: Sum the Values Table, then graph

Summary

Our dynamic VLOOKUP() method works: the manager (that's us) can replace the values in the Reference Table to update how long a project stays in each phase. We would simply repeat numbers in the Reference Table in the amount of months a project is in a particular phase. Our Values Table automatically updates based on each change.

So here's the thing. I don't like this method at all. For one, we need a VLOOKUP in for every month, for every program. Our example only displayed a few projects in a small time frame, but the real world might have many projects over many years! That's a real problem because VLOOKUPs can become computationally expensive as our spreadsheet grows.

And there's another problem, too. The manager – that's us, remember – must hand-jam the references in for every month. What if there are many years to account for? We could Copy/Paste to make life easier, but this method is so very, very error-prone. There should be a way for us to simply enter the months a project is in a given phase and have Excel automatically generate all the required reference information.

Let's talk about how to do that in the next post.

If you're having trouble with the work above, take some time to see if you can recreate your own version in Excel. Even if you have followed everything so far, consider the VLOOKUP method and the importance of using numeric references. They will play a very key role in part 2.

-----

Now Available: A Dynamic Dashboard for Project Durations and Costs in Excel (part 2)

Let’s say you are the manager of a portfolio of projects at your company. While each project under your aegis is different, they have a few things in common; specifically – and for the sake of our example – they all go through (or, are currently in) three different phases, and each phase has a different cost per month, but the cost doesn’t differ between each project. In our example, the phases are:

Phase Name Cost of each stage per monthThe idea is to capture both the cost in any given month and the overall cost over the life of the project. For example, you have an IT Upgrades project in your portfolio. You think that you will spend two months in Planning, nine months in Execution, and one month in Maturity after which the project will be closed. Thus, the overall cost of your project is expected to be,

1. Planning $250/month

2. Execution $500/month

3. Maturity $125/month

Planning @ two months: 2 months * $250 $/month = $500The problem is that each project is different. One project might spend more time in the first phase than the other. Moreover, for some projects you have a good idea of how long they will stay in each phase, and for some you are a bit less sure. Boy, you say, wouldn't it be nice to change how long a project stays in each phase to compare costs. Wouldn't it be nice to see it on a chart? Let's see what we can do.

Execution @ nine months: 9 months * $500 $/month = $4500

Maturity @ one month: 1 month * $125 $/month = $125

Planning + Execution + Maturity = $500 + $4500 + $125 = $5125

Using a VLOOKUP might seem like an obvious choice for our solution. Here's how to do it.

The Dynamic VLOOKUP Method

Step 1: Create the VLOOKUP table

Since you know there are three projects, you could encode ids into a lookup table numbers as follows.

Step 2: Create a Reference Table

The Reference Table is a time-series table that holds the numerical references to your VLOOKUP table. If IT Services has two months of Planning, then the Reference Table will show two 1's in the first two months, respectively.

Step 3: Create a Values Table to map each reference to its monthly cost using VLOOKUP

Now, you'll make another table that is essentially a mirror image of your Reference Table. This table, however, maps each reference to the correct cost. So, for Month 1 in the Values Table, VLOOKUP will use the corresponding reference (1) in the Reference Table to indicate the project is in the Planning phase and the associated cost is $250.

Step 4: Sum the Values Table, then graph

Summary

Our dynamic VLOOKUP() method works: the manager (that's us) can replace the values in the Reference Table to update how long a project stays in each phase. We would simply repeat numbers in the Reference Table in the amount of months a project is in a particular phase. Our Values Table automatically updates based on each change.

So here's the thing. I don't like this method at all. For one, we need a VLOOKUP in for every month, for every program. Our example only displayed a few projects in a small time frame, but the real world might have many projects over many years! That's a real problem because VLOOKUPs can become computationally expensive as our spreadsheet grows.

And there's another problem, too. The manager – that's us, remember – must hand-jam the references in for every month. What if there are many years to account for? We could Copy/Paste to make life easier, but this method is so very, very error-prone. There should be a way for us to simply enter the months a project is in a given phase and have Excel automatically generate all the required reference information.

Let's talk about how to do that in the next post.

If you're having trouble with the work above, take some time to see if you can recreate your own version in Excel. Even if you have followed everything so far, consider the VLOOKUP method and the importance of using numeric references. They will play a very key role in part 2.

-----

Now Available: A Dynamic Dashboard for Project Durations and Costs in Excel (part 2)